LATEST NEWS

Great Neck Fourth-Grader Wins Top Trophy At International Jewish Knowledge Championship

Naomi Cohen, a fourth-grader from Baker Hill Elementary School, recently triumphed at the International Jewish Knowledge Competition. The International Jewish Knowledge Competition, also known as JewQ, is facilitated by CKids,

Lakeville Debate Team Wins Multiple Awards At Regional Tournament

North High Student Wins SAAWA Essay Contest

South High School’s 54th Annual Opera Scheduled For April 12-13

Great Neck Park District Kicks Off Spring

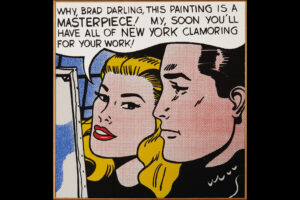

Temple Isaiah To Host Art Lecture

Suozzi Meets With Local Mayors

Top Marks For The Village Of Great Neck Plaza

Recently, Niche released its rankings for Best Places to Live for 2024. The Village of Great Neck Plaza was ranked the number one place to

Recognizing Champions

Rebels fencing secures both boys and girls Long Island Championship On Monday, March 25, the Great Neck South High School girls and boys fencing teams

Local World’s Fair Enthusiast Displays Memorabilia Collection

Jack Murphy, a sixth-grade student at Great Neck South Middle School, has become a World’s Fair enthusiast over the past couple of years. According to

Audit Of The Town Of North Hempstead’s Building Department Is Released

The Office of Nassau County Comptroller Elaine Phillips recently released its report on an audit of the Town of North Hempstead (TONH) Building Department. The

Councilmember Liu Congratulates Police On Thwarted Burglary

Town of North Hempstead Councilmember Christine Liu recently had the pleasure of meeting with and congratulating members of the Lake Success Police Department for their

The Interfaith Food Pantry Needs Your Help

To help combat food insecurity in our community, Brotherhood of Temple Beth-El of Great Neck has been partnering with the St. Aloysius Interfaith Food Pantry

TRENDING

(Photo from NBCUniversal)

Chuck Scarborough:

A Beacon of Journalistic

Longevity

By Christy Hinko • April 22, 2024

THIS WEEK'S

SPECIAL SECTIONS

UPCOMING EVENTS

- Check back for future events